OSTEOARTHRITIS

Plant Power: Do polyphenols in plants hold the answer to osteoarthritis and pain free joints?

The majority of people suffering from osteoarthritis (OA) understand that there is ‘no cure’ (1, 2) and a lifetime of drugs and eventual joint replacement surgery is inevitable (3). However, this may not be the concluding story. Recent studies are shedding nutritional light at the end of a dark osteoarthritic tunnel. Diet and supplements have been seen to manage painful OA and it’s onset but with varying success. Glucosamine sulfate as a modifying agent (4) and chondroitin are the most widely used supplements (5) but their efficacy has been disputed (6, 7). Anti-inflammatory Essential Fatty Acids (EFA’s) in oily fish are proving beneficial (8) especially more recently those found in green lipped mussels (9), and now phytonutrients and polyphenols in plants are joining the OA anti-inflammatory party (1). But can a plant really pack a punch in the treatment of osteoarthritis? Can they regenerate where other therapies have failed, or is it still just about prevention and pain relief?

What is Osteoarthritis?

OA is a ‘multifactorial’ degenerative joint disease mainly in the weight bearing mechanical joints like knees, hips, hands, lumber and cervical spine. It is the most common muscular skeletal disorder and degenerative joint disease in the elderly (10). With 8.5 million suffering in the UK (3), the incidence of OA is rising due to an ageing and increasingly obese population (11), which is the strongest modifiable risk factor (12) and is fast becoming an economic burden (1).

OA Degeneration Explained

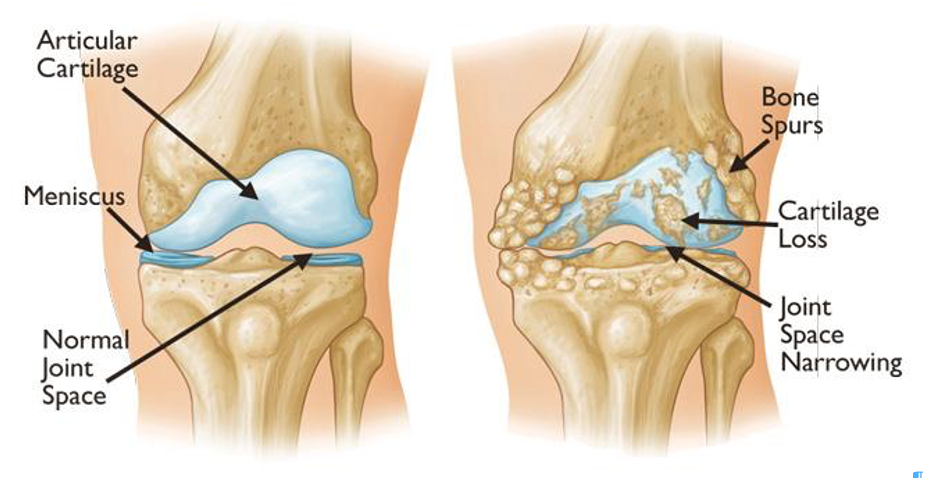

Osteoarthritic progression is cyclical and therefore slow, occurring over many years or decades. Initially, joint cartilage and surrounding tissues interact in response to the normal ageing process of ‘wear and tear’ (primary) or a pre-disposing factor like injury or deformities (secondary) (17). Joints initially appear normal but are painful and stiff especially in the mornings (18). Enzymes that increase rates of reactions, like Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP’s) degrade the joints extracellular matrix that provides structural and biochemical support to the surrounding cells, resulting in the break down of collagen fibrils (19). This decomposition triggers an increase in hydration changing the joint surface, affecting the joint capsule, subchondral bone, ligaments, muscles and tendons, including the lubricating synovial fluid, which provides oxygen and nutrients to the cartilage. Muscle weakening increases instability, which degenerates joints further with loss of the articular surface creating bone spurs causing inflammation and more pain, swelling, and loss of function (20, 21). Sufficient cartilage self-regeneration is not possible and without intervention, degeneration progresses (22).

Normal Joint Osteoarthritis

(23)

Inflammation is a vital physiological function essential to heal and protect, but with intensity and longevity it becomes pathophysiological or harmful (18). Inflammatory mediators like cytokines (Interleukin-1 (IL-1), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), prostaglandins and leukotrienes) are raised in OA so play a role in degeneration (24). Evidence suggests that osteoarthritic progress is driven by Oxidative Stress (OS), an early sign of ageing (25). Cartilage damage increases Nitric Oxide (NO) and redox derivatives like reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage cell structures. Nitric Oxide is stimulated by inflammatory cytokines further inducing apoptosis or the death of healthy chondrocytic cells (20). Worse, without sufficient dietary antioxidants like Vitamin (Vit) C, E, superoxide dismutase (SOD’s) or glutathione they cannot be neutralised and cleared from the body (26) increasing damage. Bacteria and their fermentation process also defends against toxic ROS (27).

OA Degenerative Cycle

OA Risk Factors

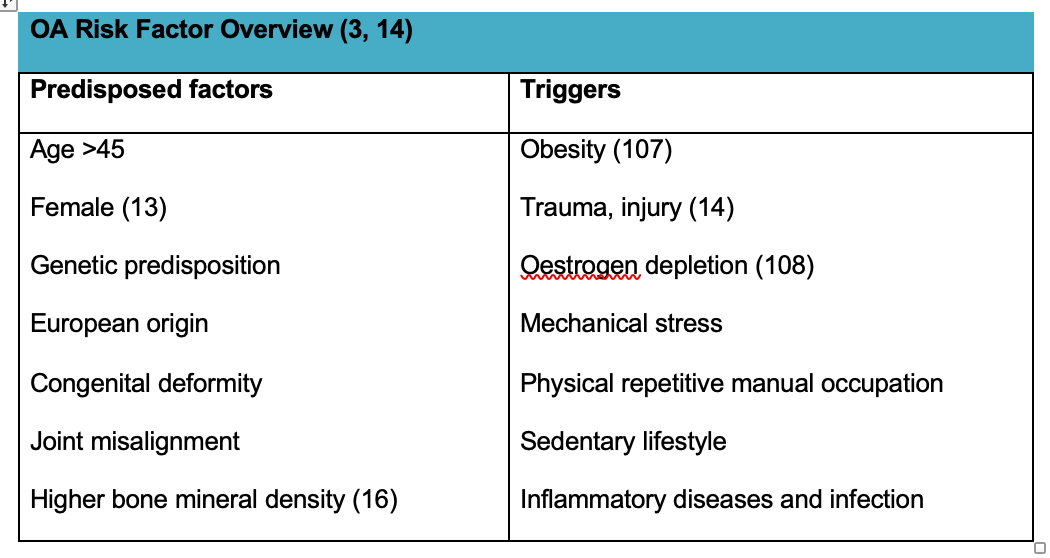

Those predisposed and more likely to suffer from OA are; over forty fives possibly due to joint misalignment, susceptibility to trauma and OS; and those with a genetic predisposition (15) like Europeans (112), women (13), congenital deformities, joint misalignment or High Bone Mineral Density phenotypes (16).

OA is more probable in obese individuals due to the extra stress on joints and release of inflammatory mediators from fat cells increasing inflammation (107). Other triggers of OA and inflammation include trauma (14) or mechanical stress (3) to joints due to repetitive manual occupations, or a sedentary lifestyle, and inflammatory diseases and infection. Oestrogen protects cartilage from inflammation so its depletion during the menopause directly affect articular cartilage and can increase triggers of OA (108).

OA Risk Factor Overview (3, 14)

OA Diagnosis & Tests

Osteoarthritis is diagnosed if a person is over 45 years and has activity related joint pain and some stiffness (14). Other physical and observational tests also diagnose osteoarthritis and blood tests, radiographs and MRI scans can establish type and extent of degeneration but do not reflect the associated pain (3)

OA Conventional Treatment

There has been a shift in medical treatment of OA to more active, patient-focused management with advice (109). It aims to include education, weight-loss advice, physiotherapy with moderate exercise, topical pain relief and gait correction (orthotics, crutches or cane) (3).

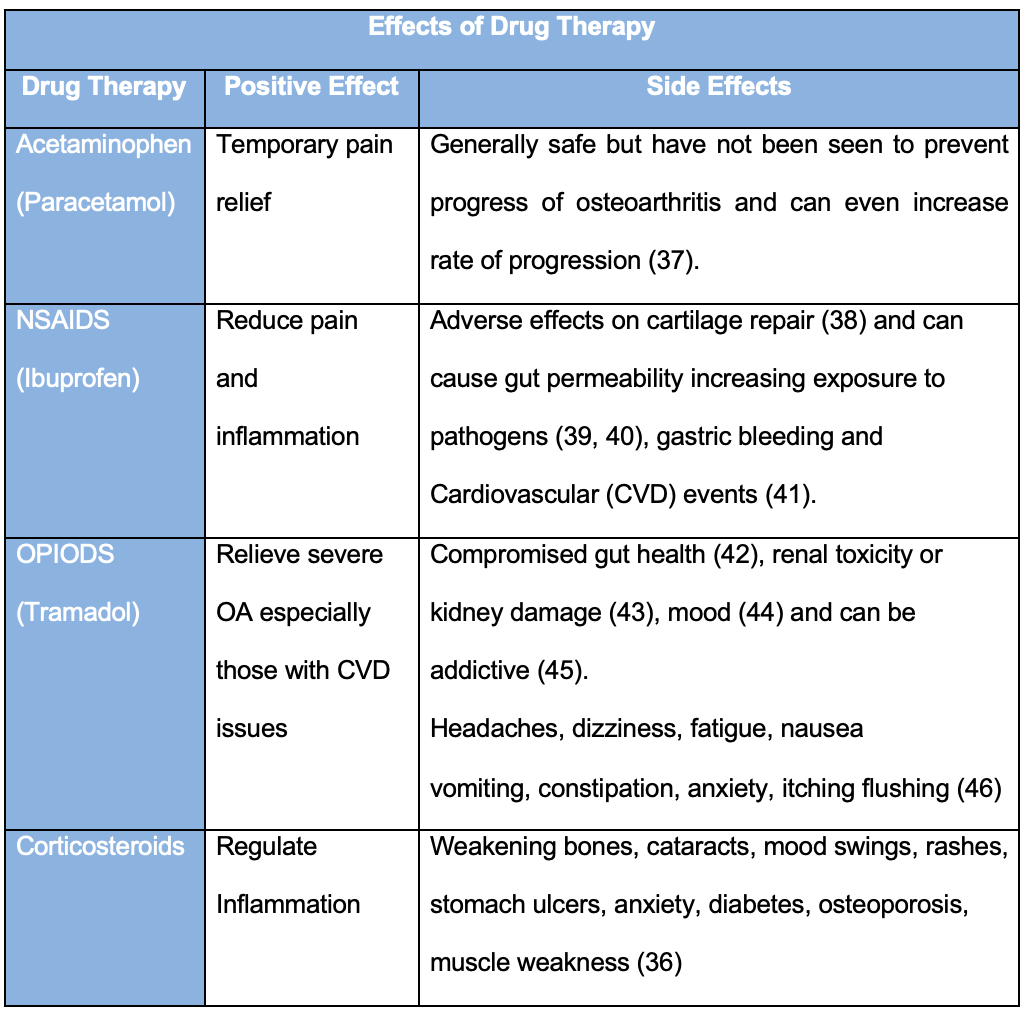

However, conventional treatment to control inflammatory pain and stiffness with drug therapy, like analgesics, is also advised. Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) works centrally on the brain temporarily reducing pain, but recent studies have identified them as having reduced effect on OA and are no longer prescribed automatically (14). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID’s) specifically inhibit inflammatory pathways like cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase (LOX) which reduces peripheral and central prostaglandins and the inflammatory response (30). In severe osteoarthritis or those with Cardiovascular (CVD) issues, opiods can relieve pain (31), these influence cerebral opiate receptor systems inducing a morphine-like effect. Tramadol for example is a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (32). Lastly, corticortisoid (33) or more controversially Hyaluronic acid (34, 35) can be injected directly into the joint and have anti-inflammatory effect on the synovium and chondrocytes (105) giving relief.

These drugs however, have adverse effects depending on the type, dose, length of use and age of client (36).

Joint replacement surgery is recommended for advanced osteoarthritis with persistent pain that affects daily life, despite drugs and alternative therapy (47, 3). Over 200,000 joint replacements are performed each year in England and Wales (48).

Due to the side effects of drugs and prospect of joint replacement surgery, it is unsurprising that 47% of OA sufferers seek further alternatives to conventional treatment including massage, saunas (24 p415, p561) or acupuncture (20; 49) as well as nutritional and supplement advice (2).

Nutritional Developments

Balancing Essential Fatty Acids (EFA’s)

It is becoming acknowledged that increasing Omega 3 EFA’s (linseeds and oily fish) balances the more common consumption of Omega 6 (vegetable oils, dairy and meat). This increase disturbs the pro-inflammatory cascade and modifies OA inflammation, OS and signs of ageing (50 p172; 51). However, the lesser known Omega 3 eicosatetranoic acid (ETA) found in Green Lipped Mussels (105) has also been seen to re-establish protective fluids within joints (8, 52). Although its mechanism of action is not clear, research suggests that its molecular structure (20:4) is so similar (53) to pro-inflammatory Arachodonic acid (AA) that it may mimic it, competing for enzymes, taking its place (54) and building anti-inflammatory protective defense fluids within joints (8, 52)

Plant Power

Phytonutrients including polyphenols are naturally occurring organic chemicals in plants (pomegranate, green tea, ginger, tumeric and rosehip) (94, 95) that protect them against their environment (55). Each plant has it’s own unique composition and therefore individual synergistic protective benefit that scientists are attempting to utilise (103). Most have antioxidant effects mopping up ROS, and others compete higher up the inflammatory pathway (56). It is thought that increasing dietary polyphenols increase systemic and tissue concentration of polyphenols that then inhibit the progression of OA (1). They are anti-inflammatory, anti-catabolic stopping muscle breakdown and protective against OS (57). They promote the increase of chondrocyte and synthesis of collagen therefore encouraging regeneration (1, 58) and are safe (110).

COX – Cyclooxygenase, CRP - C-reactive protein, GAG - Glycosaminoglycans, IL – Interleukins, MMP - matrix metalloproteinases, NO – Nitric Oxide, TNF-a - Tumor necrosis factor alpha

Polyphenols’ positive modifying effects (2) on OA symptoms, regeneration of cartilage and collagen, and inhibition of degeneration (1) gives confidence in them as a therapeutic alternative. However, it is unclear what plant and dose is required to make significant improvements, so further research is needed (2).

OA Nutritional Strategy

The earlier OA is diagnosed the better the possible outcome (59). However, at all stages of OA diagnosis it is important to reduce triggers like excess weight and mechanical stress, and mediate OS, inflammation and degeneration.

WHAT TO DO…

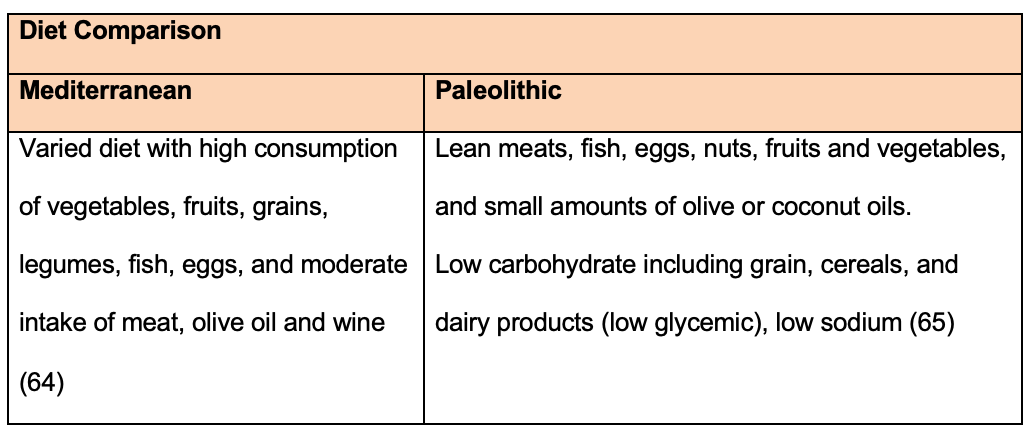

The Mediterranean (62) and Paleolithic (61) diets have been associated with improving OA (63) and they both include good quality, clean and fresh foods like fruit, vegetables, herbs and oily fish. However, a varied yet individualised nutritional and lifestyle plan should be advised, addressing specific triggers and risk factors like obesity, ageing, symptoms of inflammation, OS and degeneration (60).

Diet Comparison

Eat Plants

It is important to eat a varied diet high in colourful fruit, vegetables and herbs like berries (100), pineapple, melon, pomegranate, grapes (99), apples (98), turmeric, ginger and green tea (1). These contain antioxidants (Vit A, C, E, superoxide dismutase (SOD), Glutathione (104)) (96) and phytonutrients (polyphenols 101)) that reduce cell death and OA degeneration, decreasing OA inflammatory activity, reducing OS and signs of ageing (1, 66). Extra fibre should also regulate body weight and feed beneficial bacteria reducing inflammation (67). Red wine may also be beneficial due to its polyphenol content (68; 69).

Eat Healthy Fats

Include linseeds and oily fish, high in Omega 3 that are anti-inflammatory (51). ETA in green lipped mussels may regenerate cartilage but would need to be taken as a supplement (52).

Eat Protein

Lean meat, fish , eggs, nuts, seeds and pulses - assist muscle strength (70) and also include l-lycine which modulates joint fluids and affect inflammatory mediators in chondrocytes (71).

Add nutrients

Include nuts and seeds containing selenium required for cartilage regeneration (72). Copper (nuts), magnesium (seeds & green vegetables) (73) and manganese (pineapple) assist super antioxidant glutathione to mop up ROS and minimize OS (74). B Vits (B 6,1,2) can be found in whole-grains, improve joint mobility and muscle function (75). Beneficial bacteria in live natural yogurt (97) should also improve OA pain, inflammation and regeneration (111).

Avoid processed food

These are high in pro-inflammatory trans fatty acids and saturated fat (81), sugar which accelerates OA onset (82), refined carbohydrates like white bread and pasta, and salt. This should reduce weight, inflammation and joint degeneration (83).

Nightshade foods like potatoes, tomatoes and peppers effect 10% of arthritis sufferers so is possibly worth eliminating to assess improvements (75).

Avoid beer (84) as it could increase risks of OA.

Lifestyle

Weight-loss is important as research suggests obese individuals have greater than 40% increased risk of replacement surgery (87). Moderate exercise builds muscle tone (14) and has seen protective and anti-inflammatory benefits (89). Reducing mechanical stress, and work related repetitive or load bearing joint stressors (85) may also alleviate onset and symptoms. Physiotherapy, ultrasound, massage and sauna therapy may relieve pain (24 p415, p556, 88).

Avoid cooking at high temperatures as this produces advanced-glycation end products (AGE) increasing OS and degeneration (83, 86). Consider increasing time outside for adequate sunlight exposure improving Vit D stores, which should decrease stress fracture and muscle injury (79) and is effective for weight-loss (80) but is possibly ineffective for regeneration (76, 77, 78). Water consumption is important for general health but it has many functions in OA; it removes toxins and ROS from affected joints, helps weight loss, and improves blood circulation to relieve inflammation (90).

Suitable Tests

To help develop an even more specific dietary and lifestyle plan (93), it would be appropriate to test for; a deficiency in Vit D for general bone health, OS biomarkers like 8 hydroxy 2 decoyduanosin or telomeres (91; 92) to indicate and monitor ageing, inflammatory biomarkers (ERS, C-RP) to monitor OA progression, and an EFA profile could determine Omega 3 deficiencies.

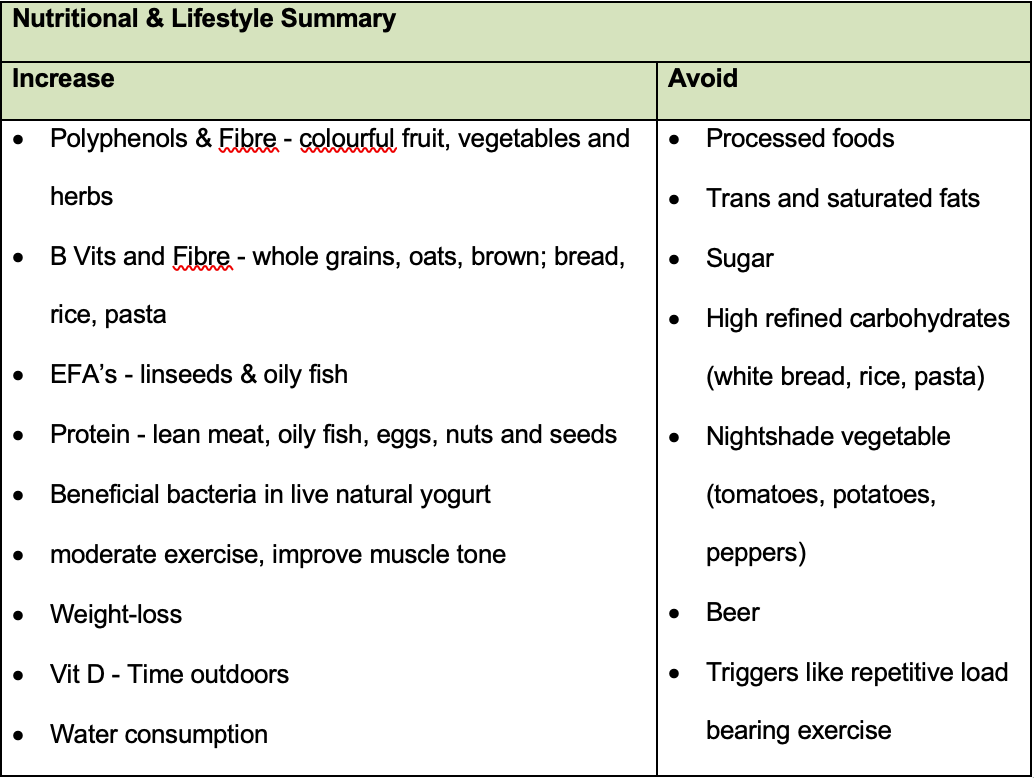

Nutritional & Lifestyle Summary

References

1. Shen CL, Smith BJ, Lo DF, Chyu MC, Dunn DM, Chen CH, Kwun IS, (2012) Dietary polyphenols and mechanisms of osteoarthritis. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry, 23(11), pp.1367-1377.

2. Leong DJ, Choudhury M, Hirsh DM, Hardin JA, Cobelli NJ, Sun HB, (2013) Nutraceuticals: potential for chondroprotection and molecular targeting of osteoarthritis. International journal of molecular sciences, 14(11), pp.23063-23085.

3. British Medical Journal (no date) Osteoarthritis. Available at: http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/192/treatment/step-by-step.html (Accessed: 10 June 2016).

4. Reginster JY, Deroisy R, Rovati LC, Lee RL, Lejeune E, Bruyere O, Giacovelli G, Henrotin Y, Dacre JE, Gossett C (2001) Long-term effects of glucosamine sulphate on osteoarthritis progression: a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. The Lancet, 357(9252), pp.251-256.

5. Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, Klein MA, O'Dell JR, Hooper MM, Bradley JD, Bingham III CO, Weisman MH, Jackson CG, Lane NE (2006) Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. New England Journal of Medicine, 354(8), pp.795-808.

6. Wu D, Huang Y, Gu Y, Fan W (2013) Efficacies of different preparations of glucosamine for the treatment of osteoarthritis: a meta‐analysis of randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials. International journal of clinical practice, 67(6), pp.585-594.

7. Singh J, MacDonald R, Maxwell LJ, Noorbaloochi S (2015) ‘Chondroitin for osteoarthritis’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, . doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd005614.pub2.

8. Servet E, Biourge V, Marniquet P (2006) Dietary intervention can improve clinical signs in osteoarthritic dogs. The Journal of nutrition, 136(7), pp.1995S-1997S.

9. Kean JD, Camfield D, Sarris J, Kras M, Silberstein R, Scholey A, Stough C (2013) A randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of PCSO-524®, a patented oil extract of the New Zealand green lipped mussel (Perna canaliculus), on the behaviour, mood, cognition and neurophysiology of children and adolescents (aged 6–14 years) experiencing clinical and sub-clinical levels of hyperactivity and inattention: study protocol ACTRN12610000978066. Nutrition journal, 12(1), p.1.

10. Busija L, Bridgett L, Williams S, Osborne R, Buchbinder R, March L, Fransen M (2011) ‘Osteoarthritis’, Best practice & research. Clinical rheumatology., 24(6), pp. 757–68.

11. Alizai H, Roemer RW, Hayashi D, Crema MD, Felson DT, Guermazi A (2015) An update on risk factors for cartilage loss in knee osteoarthritis assessed using MRI-based semiquantitative grading methods. European radiology, 25(3), pp.883-893.

12. Schilling R (2015) Obesity Shortens life [online] available from <http://www.askdrray.com/obesity-shortens-life/> [22 June 2016]

13. Silverwood, V., Blagojevic-Bucknall, M., Jinks, C., Jordan, J.L., Protheroe, J. and Jordan, K.P., 2015. Current evidence on risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 23(4), pp.507-515.

14. National Institute for Clinical Excellence and National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2014) Osteoarthritis: care and management in adults. London, UK: National Institute for Clinical Excellence.

15. Shen JM, Feng L, Feng C (2014) Role of mtDNA Haplogroups in the Prevalence of Osteoarthritis in Different Geographic Populations: A Meta-Analysis. PloS one, 9(10).

16. Boyden LM, Mao J, Belsky J, Mitzner L, Farhi A, Mitnick MA, Wu D, Insogna K, Lifton RP (2002) High bone density due to a mutation in LDL-receptor–related protein 5. New England Journal of Medicine, 346(20), pp.1513-1521.

17. Roelofs, A.J., Rocke, J.P.J. and De Bari, C., 2013. Cell-based approaches to joint surface repair: a research perspective. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 21(7), pp.892-900.

18. Murray M, Pizzorno JE, Pizzorno LU (2008) The encyclopaedia of healing foods. London: Piatkus Books.

19. Ruettger A, Schueler S, Mollenhauer JA, Wiederanders B (2008) Cathepsins B, K, and L are regulated by a defined collagen type II peptide via activation of classical protein kinase C and p38 MAP kinase in articular chondrocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283(2), pp.1043-1051

20. Maldonado M & Nam J (2013) The role of changes in extracellular matrix of cartilage in the presence of inflammation on the pathology of osteoarthritis. BioMed research international, 2013.

21. Huang, K. and Wu, L.D., 2008. Aggrecanase and aggrecan degradation in osteoarthritis: a review. Journal of International Medical Research, 36(6), pp.1149-1160.

22. Sakata R, Iwakura T, Reddi AH (2015) Regeneration of articular cartilage surface: Morphogens, cells, and extracellular matrix scaffolds. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews, 21(5), pp.461-473.

23. Orthoinfo (2014) Arthritis of the Knee-OrthoInfo. Available at: http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00212 (Accessed: 10 June 2016).

24. Jones DS, Baker SM, Bennett P, Bl JS, Gall L, Hedaya RJ, Houston M, Hyman M, Lombard J, Rountree R, Vasquez A (2005) Textbook of functional medicine. 2nd edn. Gig Harbor, WA.: Institute for functional medicine.

25. Conti V, Corbi G, Simeon V, Russomanno G, Manzo V, Ferrara N, Filippelli A (2015) Aging-related changes in oxidative stress response of human endothelial cells. Aging clinical and experimental research, 27(4), pp.547-553.

26. Deberg M, Labasse A, Christgau S, Cloos P, Henriksen DB, Chapelle JP, Zegels B, Reginster JY, Henrotin Y (2005) New serum biochemical markers (Coll 2-1 and Coll 2-1 NO 2) for studying oxidative-related type II collagen network degradation in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoarthritis and cartilage, 13(3), pp.258-265.

27. Wang CY, Wu SJ, Shyu YT (2014) Antioxidant properties of certain cereals as affected by food-grade bacteria fermentation. Journal of bioscience and bioengineering, 117(4), pp.449-456.

28. Lintbells (2016) How to ease joint pain in dogs & cats / Lintbells Blog [online] available from <http://www.lintbells.com/articles/how-to-ease-joint-pain-in-dogs--cats#.V1lIF0I49UQ> [23 June 2016]

29. Luyten FP, Denti M, Filardo G, Kon E, Engebretsen L (2012) Definition and classification of early osteoarthritis of the knee. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 20(3), pp.401-406.

30. Conaghan PG (2012) A turbulent decade for NSAIDs: update on current concepts of classification, epidemiology, comparative efficacy, and toxicity. Rheumatology international, 32(6), pp.1491-1502.

31. da Costa BR, Nuesch E, Kasteler R, Husni E, Welch V, Rutjes AW, Juni P (2014) Oral or transdermal opioids for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 9.

32. Smith HS, Raffa RB, Pergolizzi JV, Taylor R, Tallarida RJ (2014) Combining opioid and adrenergic mechanisms for chronic pain. Postgraduate medicine, 126(4), pp.98-114.

33. Hall M, Doherty S, Courtney P, Latief K, Zhang W, Doherty M (2014) Ultrasound detected synovial change and pain response following intra-articular injection of corticosteroid and a placebo in symptomatic osteoarthritic knees: a pilot study. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, pp.annrheumdis-2014.

34. Balogh L, Polyak A, Mathe D, Kiraly R, Thuroczy J, Terez M, Janoki G, Ting Y, Bucci LR, Schauss AG (2008) Absorption, uptake and tissue affinity of high-molecular-weight hyaluronan after oral administration in rats and dogs. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 56(22), pp.10582-10593.

35. Elmorsy S, Funakoshi T, Sasazawa F, Todoh M, Tadano S, Iwasaki N, (2014) Chondroprotective effects of high-molecular-weight cross-linked hyaluronic acid in a rabbit knee osteoarthritis model. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 22(1), pp.121-127.

36. NHS Choices (2016) Corticosteroids - side effects. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Corticosteroid-(drugs)/pages/sideeffects.aspx (Accessed: 20 June 2016).

37. Hunter DJ & Ferreira ML (2016) Osteoarthritis: Yet another death knell for paracetamol in OA. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 12(6), pp.320-321.

38. Arends RH, Karsdal MA, Verburg KM, Bay-Jensen AC, West CR, Keller DS (2016) Biomarkers associated with rapid cartilage loss and bone destruction in osteoarthritis patients. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 24, p.S53.

39. Ray-Yee Yap P & Goh KL (2015) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) induced Dyspepsia. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 21(35), pp.5073-5081.

40. Yoshikawa K, Kurihara C, Furuhashi H, Takajo T, Maruta K, Yasutake Y, Sato H, Narimatsu K, Okada Y, Higashiyama M, Watanabe C (2016) Psychological stress exacerbates NSAID-induced small bowel injury by inducing changes in intestinal microbiota and permeability via glucocorticoid receptor signaling. Journal of gastroenterology, pp.1-11.

41. Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, Hildebrand P, Tschannen B, Villiger PM, Egger M, Jüni P (2011) Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. Bmj, 342, p.c7086.

42. Marlicz W, Łoniewski I, Grimes DS, Quigley EM (2014) December. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitors, and gastrointestinal injury: contrasting interactions in the stomach and small intestine. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Vol. 89, No. 12, pp. 1699-1709). Elsevier.

43. Crofford LJ (2013) Use of NSAIDs in treating patients with arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther, 15(Suppl 3), p.S2.

44. Stephan BC & Parsa FD (2016) Avoiding Opioids and Their Harmful Side Effects in the Postoperative Patient: Exogenous Opioids, Endogenous Endorphins, Wellness, Mood, and Their Relation to Postoperative Pain. Hawai'i Journal of Medicine & Public Health, 75(3), p.63.

45. Doherty M, Hawkey C, Goulder M, Gibb I, Hill N, Aspley S, Reader S, (2011) A randomised controlled trial of ibuprofen, paracetamol or a combination tablet of ibuprofen/paracetamol in community-derived people with knee pain. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 70(9), pp.1534-1541.

46. NHS Choices (2016b) Peripheral neuropathy - treatment. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Peripheral-neuropathy/Pages/Treatment.aspx (Accessed: 20 June 2016).

47. de l’Escalopier N, Anract P, Biau D (2016) Surgical treatments for osteoarthritis. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine.

48. National Joint Registry, Esler C, Howard P, Rees J, Porteous M, Goldberg A, Kulkarni Rangan A, Rees J, Beaumont R, Thornton J, Young E, Mccormack V, Mistry A, Newell C, Pickford M, Royall M, Swanson M, Ben Y, Shlomo Blom A, Clark E, Dieppe P, Hunt L, King G, Whitehouse M (2015) 12th Annual Report 2015. Available at: http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/Portals/0/Documents/England/Reports/12th%20annual%20report/NJR%20Online%20Annual%20Report%202015.pdf (Accessed: 20 June 2016).

49. McAlindon TE, Bannuru R, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Hawker GA, Henrotin Y, Hunter DJ, Kawaguchi H, Kwoh K, (2014) OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 22(3), pp.363-388.

50. Gropper SS & Smith JL (2012) Advanced nutrition and human metabolism. Cengage Learning.

51. Brouwers H, von Hegedus J, Toes R, Kloppenburg M, Ioan-Facsinay A, (2015) Lipid mediators of inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 29(6), pp.741-755.

52. Grienke U, Silke J, Tasdemir D (2014) Bioactive compounds from marine mussels and their effects on human health. Food chemistry, 142, pp.48-60.

53. Rustan AC & Drevon CA (2005) Fatty acids: structures and properties. eLS.

54. Lorgeril MED (2007) Essential polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases. In Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Chronic Diseases (pp. 283-297). Springer Netherlands.

55. Miedes E, Vanholme R, Boerjan W, Molina A (2015) The role of the secondary cell wall in plant resistance to pathogens. Plant cell wall in pathogenesis, parasitism and symbiosis, p.78.

56. Ghoochani N, Karandish M, Mowla K, Haghighizadeh MH, Jalali MT (2016) The effect of pomegranate juice on clinical signs, matrix metalloproteinases and antioxidant status in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture.

57. Mobasheri A, Shakibaei M, Biesalski HK, Henrotin Y (2013) Antioxidants in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis and Bone Mineral Loss. In Studies on Arthritis and Joint Disorders (pp. 275-295). Springer New York.

58. Natarajan V, Madhan B, Tiku ML (2015) Intra-articular injections of polyphenols protect articular cartilage from inflammation-induced degradation: suggesting a potential role in cartilage therapeutics. PloS one, 10(6), p.e0127165.

59. Losina E, Weinstein AM, Reichmann WM, Burbine SA, Solomon DH, Daigle ME, Rome BN, Chen SP, Hunter DJ, Suter LG, Jordan JM (2013) Lifetime risk and age at diagnosis of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US. Arthritis care & research, 65(5), pp.703-711.

60. Poulet B & Beier F (2016) Targeting oxidative stress to reduce osteoarthritis. Arthritis research & therapy, 18(1), p.1.

61. Cordain L & Friel J (2012) The paleo diet for athletes: The ancient nutritional formula for peak athletic performance. Rodale.

62. Whalen K, McCullough M, Flanders WD, Hartman TJ, Judd S, Bostick RM (2015) Paleolithic and Mediterranean diet pattern scores and their associations with biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative balance. Cancer Research, 75(15 Supplement), pp.1889-1889.

63. Dyer J, Davison G, Marcora SM, Mauger A (2016) Effect of a Mediterranean type diet on inflammatory and cartilage degradation biomarkers in patients with osteoarthritis. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging.

64. Altomare R, Cacciabaudo F, Damiano G, Palumbo VD, Gioviale MC, Bellavia M, Tomasello G, Monte AIL (2013) The mediterranean diet: a history of health. Iranian journal of public health, 42(5), p.449.

65. Genoni A, Lyons-Wall P, Lo J, Devine A (2016) Cardiovascular, Metabolic Effects and Dietary Composition of Ad-Libitum Paleolithic vs. Australian Guide to Healthy Eating Diets: A 4-Week Randomised Trial. Nutrients, 8(5), p.314.

66. Vyas S, Sharma H, Vyas RK, Chawla K, Jaipal M (2015) Oxidative stress and antioxidant level in the serum of osteoarthritis patients. Indian Journal of Scientific Research, 6(1), p.37.

67. Tuohy KM, Conterno L, Gasperotti M, Viola R (2012) Up-regulating the human intestinal microbiome using whole plant foods, polyphenols, and/or fiber. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 60(36), pp.8776-8782.

68. Chiva-Blanch G, Urpi-Sarda M, Llorach R, Rotches-Ribalta M, Guillén M, Casas R, Arranz S, Valderas-Martinez P, Portoles O, Corella D, Tinahones F (2012) Differential effects of polyphenols and alcohol of red wine on the expression of adhesion molecules and inflammatory cytokines related to atherosclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 95(2), pp.326-334.

69. Kutleša Z & Mršić DB (2016) Wine and bone health: a review. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism, 34(1), pp.11-22.

70. Daly RM, O'Connell SL, Mundell NL, Grimes CA, Dunstan DW, Nowson CA (2014) Protein-enriched diet, with the use of lean red meat, combined with progressive resistance training enhances lean tissue mass and muscle strength and reduces circulating IL-6 concentrations in elderly women: a cluster randomized controlled trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 99(4), pp.899-910.

71. Huang TL, Wu CC, Yu J, Sumi S, Yang KC (2016) L-Lysine regulates tumor necrosis factor-alpha and matrix metalloproteinase-3 expression in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Process Biochemistry, 51(7), pp.904-911.

72. Bissardon C, Charlet L, Bohic S, Khan I (2015) October. Role of the selenium in articular cartilage metabolism, growth, and maturation. In Global Advances in Selenium Research from Theory to Application: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Selenium in the Environment and Human Health 2015 (p. 77). CRC Press.

73. Zeng C, Li H, Wei J, Yang T, Deng ZH, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Yang TB, Lei GH (2015) Association between dietary magnesium intake and radiographic knee osteoarthritis. PLoS One, 10(5), p.e0127666.

74. Katti SA, Suravanshi AK, Bangar SS, Sanakal D, Surendran S (2015) A Study of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Levels in Osteoarthritis. International Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Research, 2(4), pp.236-241.

75. Prousky JE (2015) The use of Niacinamide and Solanaceae (Nightshade) Elimination in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. JOM, 30(1), p.13.

76. McAlindon T, LaValley M, Schneider E, Nuite M, Lee JY, Price LL, Lo G, Dawson-Hughes B (2013) Effect of vitamin D supplementation on progression of knee pain and cartilage volume loss in patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 309(2), pp.155-162.

77. Arden NK, Cro S, Sheard S, Doré CJ, Bara A, Tebbs SA, Hunter DJ, James S, Cooper C, O’Neill TW, Macgregor A (2016) The effect of vitamin D supplementation on knee osteoarthritis, the VIDEO study: a randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage.

78. Bergink AP, Zillikens MC, Van Leeuwen JP, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, van Meurs JB (2016) April. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis including new data. In Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism (Vol. 45, No. 5, pp. 539-546). WB Saunders.

79. Ogan D & Pritchett K (2013) Vitamin D and the athlete: risks, recommendations, and benefits. Nutrients, 5(6), pp.1856-1868.

80. Christakos S, Hewison M, Gardner DG, Wagner CL, Sergeev IN, Rutten E, Pittas AG, Boland R, Ferrucci L & Bikle DD (2013) Vitamin D: beyond bone. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1287(1), pp.45-58.

81. Lu B, Driban JB, Xu C, Lapane KL, McAlindon TE, Eaton CB (2016) Dietary Fat and Progression of Knee Osteoarthritis Dietary Fat Intake and Radiographic Progression of Knee Osteoarthritis: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis care & research.

82. Tick H (2015) Nutrition and Pain. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America, 26(2), pp.309-320.

83. Sharma C, Kaur A, Thind SS, Singh B, Raina S (2015) Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs): an emerging concern for processed food industries. Journal of food science and technology, 52(12), pp.7561-7576.

84. Muthuri SG, Zhang W, Maciewicz RA, Muir K, Doherty M (2015) Beer and wine consumption and risk of knee or hip osteoarthritis: a case control study. Arthritis research & therapy, 17(1), p.1.

85. Buckwalter JA, Anderson DD, Brown TD, Tochigi Y, Martin JA (2013) The roles of mechanical stresses in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: implications for treatment of joint injuries. Cartilage, p.1947603513495889.

86. Ansari MY & Haqqi TM (2015) Advanced glycation end products (ages) induce stress granule assembly in human OA chondrocytes that captures mRNAS associated with osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 23, p.A157.

87. Leyland KM, Judge A, Javaid MK, Diez‐Perez A, Carr A, Cooper C, Arden NK, Prieto‐Alhambra D (2016) Obesity and the Relative Risk of Knee Replacement Surgery in Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Prospective Cohort Study. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 68(4), pp.817-825.

88. Rutjes AW, Nüesch E, Sterchi R, Jüni P (2010) Therapeutic ultrasound for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. The Cochrane Library.

89. Messier SP, Callahan LF, Golightly YM, Keefe FJ (2015) OARSI Clinical Trials Recommendations: Design and conduct of clinical trials of lifestyle diet and exercise interventions for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 23(5), pp.787-797.

90. Popkin BM, D'Anci KE, Rosenberg IH (2010) Water, hydration, and health. Nutrition reviews, 68(8), pp.439-458.

91. Syslová K, Böhmová A, Mikoška M, Kuzma M, Pelclová D, Kačer P (2014) Multimarker screening of oxidative stress in aging. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2014.

92. Yui N, Yudoh K, Fujiya H, Musha H (2016) Mechanical and oxidative stress in osteoarthritis. The Journal of Physical Fitness and Sports Medicine, 5(1), pp.81-86.

93. Al-Okbi SY (2012) Nutraceuticals of anti-inflammatory activity as complementary therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Toxicology and industrial health, p.0748233712462468.

94. Xu Y, Zhang M, Wu T, Dai S, Xu J, Zhou Z (2015) The anti-obesity effect of green tea polysaccharides, polyphenols and caffeine in rats fed with a high-fat diet. Food & function, 6(1), pp.296-303.

95. Zhong HM, Ding QH, Chen WP, Luo RB (2013) Vorinostat, a HDAC inhibitor, showed anti-osteoarthritic activities through inhibition of iNOS and MMP expression, p38 and ERK phosphorylation and blocking NF-κB nuclear translocation. International immunopharmacology, 17(2), pp.329-335.

96. Suantawee T, Tantavisut S, Adisakwattana S, Tanavalee A, Yuktanandana P, Anomasiri W, Deepaisarnsakul B, Honsawek S (2013) Oxidative stress, vitamin e, and antioxidant capacity in knee osteoarthritis. J Clin Diagn Res, 7(9), pp.1855-1859.

97. So, J.S., Song, M.K., Kwon, H.K., Lee, C.G., Chae, C.S., Sahoo, A., Jash, A., Lee, S.H., Park, Z.Y. and Im, S.H., 2011. Lactobacillus casei enhances type II collagen/glucosamine-mediated suppression of inflammatory responses in experimental osteoarthritis. Life sciences, 88(7), pp.358-366.

98. Masuda, I., 2016. Apple polyphenols protect cartilage degeneration through modulating mitochondrial function in mice. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 24, pp.S354-S355

99. Lucero J, Vijayagopal P, Juma S (2014) Chondroprotective role of whole grape polyphenols in stimulated SW 1353 cells (830.27). The FASEB Journal, 28(1 Supplement), pp.830-27.

100. Koli R, Erlund I, Jula A, Marniemi J, Mattila P, Alfthan G (2010) Bioavailability of Various Polyphenols from a Diet Containing Moderate Amounts of Berries†. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 58(7), pp.3927-3932.

101. Im HJ, Li X, Chen D, Yan D, Kim J, Ellman MB, Stein GS, Cole B, Kc R, Cs‐Szabo G, van Wijnen AJ (2012) Biological effects of the plant‐derived polyphenol resveratrol in human articular cartilage and chondrosarcoma cells. Journal of cellular physiology, 227(10), pp.3488-3497.

102. Hoxha F, Tafaj A, Roshi E, Burazeri G (2015) Distribution of Risk Factors in Male and Female Primary Health Care Patients with Osteoarthritis in Albania. Medical Archives, 69(3), p.145.

103. Henderson TR, Lippiello L, Filburn C, Griffin D, Nutramax Laboratories Inc (2014) Combination of unsaponifiable lipids combined with polyphenols and/or catechins for the protection, treatment and repair of cartilage in joints of humans and animals. U.S. Patent Application 14/296,031.

104. Gomes EC, Silva AN, Oliveira MRD (2012) Oxidants, antioxidants, and the beneficial roles of exercise-induced production of reactive species. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2012.

105. Fakhari A & Berkland C (2013) Applications and emerging trends of hyaluronic acid in tissue engineering, as a dermal filler and in osteoarthritis treatment. Acta biomaterialia, 9(7), pp.7081-7092.

106. Chakraborty M, Bhattacharya S, Mishra R, Saha SS, Bhattacharjee P, Dhar P, Mishra R (2015) Combination of low dose major n3 PUFAs in fresh water mussel lipid is an alternative of EPA–DHA supplementation in inflammatory conditions of arthritis and LPS stimulated macrophages. PharmaNutrition, 3(2), pp.67-75.

107. Berenbaum F, Eymard F, Houard X (2013) Osteoarthritis, inflammation and obesity. Current opinion in rheumatology, 25(1), pp.114-118.

108. Sniekers YH, Weinans H, van Osch GJ, van Leeuwen JP (2010) Oestrogen is important for maintenance of cartilage and subchondral bone in a murine model of knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis research & therapy, 12(5), p.1.

109. Howells N & Birrell, F (2011) Osteoarthritis: a modern approach to diagnosis and management.

110. Espitia PJ, Avena‐Bustillos RJ, Du WX, Chiou BS, Williams TG, Wood D, McHugh TH, Soares NF (2014) Physical and antibacterial properties of Açaí edible films formulated with thyme essential oil and apple skin polyphenols. Journal of food science, 79(5), pp.M903-M910.

111. Bravo-Blas A, Wessel H, Milling S (2016) Microbiota and arthritis: correlations or cause?. Current opinion in rheumatology, 28(2), pp.161-167.

112. Hoaglund FT (2013) Primary osteoarthritis of the hip: a genetic disease caused by European genetic variants. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 95(5), pp.463-468.